From the back row of a local movie theater, sitting between Kath and my buddy Chris, I looked hard to find on the big screen my mentor I’ll always know by one name.

Howard.

I couldn’t pick Howard out – or at least not the actor who portrayed him. All I saw during the film was a crowd of people around clattering typewriters in a replica of 1970s newsroom full of bangs and what looked like a beehive.

So, I waited until the closing credits rolled, and there I saw it — Howard was played by an actor named David Cross.

Who?

I looked up David Cross up when I got home. He wore a lot of makeup for his role as Howard, and he looked nothing like the Howard I knew.

David Cross

Howard Simons

And yet ….

David Cross had slipped into my mentor’s skin and took on a role that will always resonate with me because of a time past.

When I thought about all that, I winced. I had told Howard thank you several times. But I never said good-bye.

He was one of my journo mentors, a man I went to ask, to laugh with, to understand why I needed to carry constantly a notebook in my hands and ask questions that mine for the truth.

That man was Howard Simons, known as Ben Bradlee’s secret weapon at The Washington Post during the 1970s.

Howard was the deputy managing editor when WaPo printed the Pentagon Papers in 1971. That’s the plot of “The Post,” a shoo-in for a shelf of Oscars.

You’ll find an excerpt from a new book about it here.

A few months later, Howard became the paper’s managing editor. He held that post for 13 years, steering the newsroom from 400 to 550 people during his tenure.

Matter of fact, he got the fateful phone call about the Watergate burglary from a close friend. That’s how it began.

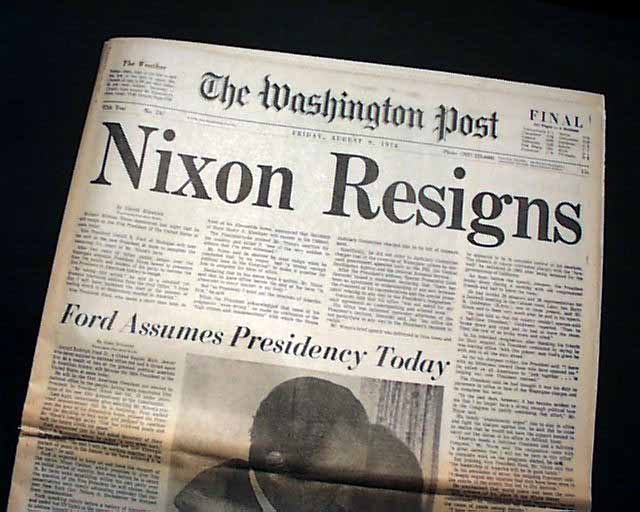

He worked with reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward and helped direct the paper’s investigation into a conspiracy that led to the resignation of a U.S. president.

How ‘bout that for a front page?

More than a decade later after managing Woodward and Bernstein and making history, Howard met me.

I was an undergrad at the University of South Carolina, working as an intern in the president’s office.

Basically, that meant I had a job where I wore a suit, wrote letters, made coffee, spirited packages across campus and hung out in a back office with other interns listening to Prince and Bruce Springsteen, U2 and The Moody Blues.

We interns also escorted the political big wheels who came to campus. That’s how I met Howard.

This is how I remember it: My intern coordinator popped his head into our intern office, saw me – the one journalism student in our intern bunch – and asked, “This guy, Howard. Howard Simons. You know him?”

Like yeah, I told him.

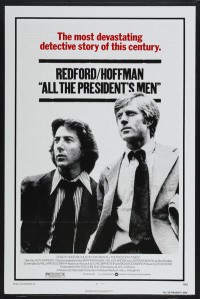

I came of age in a generation of wanna-be journalists who saw “All The President’s Men” as the oysters in our stew. That book and later the movie spurred so many people I know to jump into the profession.

Of course, I was one of them.

So, yeah, I told my intern coordinator, I knew Howard.

That’s how it began with Howard and his wife, Tod.

They both were funny, engaging, quick witted as ever. They’d go back and forth in conversations with me, no airs at all. When I think back, the one thing I remember about Howard were the laugh lines around his eyes.

His eyes seemed to be smiling. Always smiling.

Back then, Howard had left his post as WaPo’s managing editor to become the curator for the Nieman Foundation, the school for mid-career journalists at Harvard. That was a big deal. He was a big deal.

But you wouldn’t know it. He was just Howard, a guy always full of questions.

With me, he wanted to know what it was like growing up in the South, going to school in the South and being really the first generation of Southerners to sit side by side with blacks in class.

Then, he asked if I wanted to go running.

We did.

We ran on weekday mornings, and our route was often the same. We’d start from somewhere near USC’s Horseshoe.

USC’s Horseshoe.

Then, we’d head north toward the grounds of the State House and pass the ginormous statue of Wade Hampton, the confederate general and former governor.

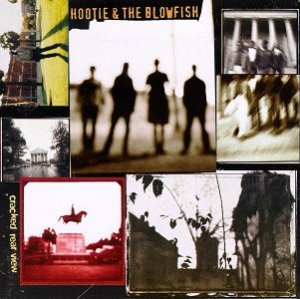

You’ve probably seen it. It’s the same statue that’s on the album cover of “Cracked Rear View,” the debut recording from Hootie & The Blowfish that sold like a gazillion copies.

Plus, if you’ve ever been to South Carolina’s capital city of Columbia, there is no WAY you can miss it. That Hampton statue is huge.

Now, back to Howard.

On our second or third run, I turned to Howard and asked a question I always wanted to know.

See, Howard had named Woodward’s source “Deep Throat” after Linda Lovelace’s X-rated film. But back then, no one knew who “Deep Throat” was – and everybody wanted to know.

So, being the headstrong college student brave enough to ask stupid questions, I asked.

“So, who was Deep Throat?”

I kept running and noticed Howard was nowhere near my left shoulder. I turned around and saw him smiling at me, hands on his hips, head cocked in a way that said “You dumb ass!”

“Rowe,” he said. “You think I’m going to tell you?”

He didn’t. We kept running.

At USC, he went on to lecture or teach a graduate level journalism course, I believe, for a semester or two. I can’t remember. But what I do remember is this:

I’d see him in the dungeon of the USC’s journalism school underneath the Carolina Coliseum’s Frank McGuire Arena, and we’d stop and talk about everything – classes, career advice, even Deep Throat.

And the Capitol Restaurant.

That was across the street from the State House.

Howard did love that place. I knew it for late-night eats like fried chicken and brains and eggs. Howard knew it for what I remember was its bluegrass jams late at night.

A classically Southern place now closed.

In 1986, five months after leaving USC with a journalism degree in hand, I landed a reporting job with a daily newspaper in Framingham, Mass., a huge town 30 minutes or so west of Boston.

I threw everything into my Gamecock red VW Golf and moved 14 hours north. A few months into my new job, I looked up the number for the Nieman Foundation and called Howard.

That was fun. We talked. Laughed, too. Then, he mentioned that I should come see him. Sure, I said.

“How do I find you?” I asked.

He paused, laughed and responded.

“You’re a reporter,” he said. “Find me.”

Then, he hung up.

Oh, I found him. In the years way before Google Maps, I went old school.

Pulled out a telephone book, plopped a map Atlas of Cambridge across my kitchen table, drove over the Charles River, parked on a side street that felt like a wind tunnel and asked a few people for directions — from Harvard Square all the way to the steps of the Walter Lippman House, Nieman’s headquarters.

From what I remember, I got there a few minutes early. I walked into his office, and when he saw me, he looked up and laughed.

“You found me!” he said. “Rowe, you’re better than I thought!”

I’ve told that story more than a few times to journalists I’ve worked with. It always makes me laugh. It also makes me remember.

I saw Howard one more time after that. It was a weekday morning, his office was dark and Howard was subdued. I was too cautious to ask why. Felt it was none of my business.

We talked about the usual stuff — my assignments, his family, his reporting advice, his career, his career advice and his idea that all stories need to make readers go, “Holy shit!”

Then, I left.

That was the last time I saw Howard.

Like many young journalists, I buried myself in my work. I got a promotion and scored a plum assignment covering a blue-collar city west of Boston with rough-and-tumble politics that parked me in a high-ceiling courtroom in Boston’s Financial District, writing about what was then the largest bank fraud in New England history.

Straight out of “The Sopranos” that thing was.

Meanwhile, I always looked forward to Friday nights. I joined my newsroom friends and conducted what we liked to call “Choir Practice.”

We all were pretty poor in the pocket. So, we’d get together at a friend’s apartment, drink copious amounts of cheap beer, suck down shots of tequila like water and talk way past midnight about the countless stories we wrote that week.

And we all wrote lots of stories.

My choir members. And yeah, that’s me in the back with the black eye, the outcome of driving to the hoop every Saturday afternoon at Boston College’s cavernous student gym.

By then, Howard had become a good memory. But I always knew if I needed a quick sit with him, asking him to advise, to run, to do anything, I figured he was only a few T stops away from my cozy second-floor apartment in Brighton.

Then, one day in June 1989, I opened my Boston Globe to the editorial section and felt like I got punched in the gut.

The man Ben Bradlee called a “powerhouse.”

The man Kay Graham saw as a “brilliant writer and editor.”

The man who made me laugh and think about how the stories I write need to make readers yell “Holy shit!”

Howard Simons had died.

He was taken down by pancreatic cancer after moving to Florida when a doctor gave him a grim diagnosis. Howard declined treatment – and this decision came from an old science writer.

But he knew his days were numbered, and he wanted them filled with unabashed joy, not 20th century medicine. So, during his final days, Howard simply wanted to fish and bird watch.

A month or so after he got his diagnosis, Howard Simons died with his family around him. He was 60.

You’ll find his obit here.

“He was the quintessential nurturer of talent,” Derek Bok, president of Harvard, said of Simons in The Boston Globe right after his death. “He chastised those who settled for second best, praised those who pursued excellence and inspired virtually every young journalist with whom he came in contact.”

I was one of those young journalists.

That mentorship is still continuing. Eleven years after his death, the University of Maryland established a graduate fellowship in his name. You’ll find out more about it here.

That brings me back to the back row of a darkened movie theater five minutes from my house.

After “The Post” ended, I stayed. I knew I had to see the name of Howard Simons in the closing credits.

When I saw it, I thought back to our morning runs, our conversations in USC’s J-School dungeon and my frantic search for his office at Harvard one weekday morning decades ago.

Those moments. All good memories.

Afterward, like any journalist, I went searching for more. That’s when I found what Bob Woodward said about Howard right after his death.

Howard was “the day-to-day agitator, the one who ran around the newsroom inspiring, shouting, directing, insisting that we not abandon our inquiry, whatever the level of denials or denunciations.”

Or this from David Broder, WaPo’s longtime political writer.

“I think of Howard moving across the newsroom with that sort of Groucho Marx stride of his, stopping probably 20 times between the {managing editor’s} office and the men’s room — if that’s where he was headed — to listen to somebody’s tale of woe, congratulate somebody, or whatever.

“He provided so much of the human touch.”

Nice.

In an era when our president shouts “Fake news!” at any story about him he doesn’t like, when he sees reporters as the “enemy of the people” and has essentially I believe made it fair game to insult, body-slam or punch any reporter for doing their job, I wonder what Howard would think about all that.

I’ve got an idea.

Take a stand, he’d say.

Print the truth and raise hell.

Don’t back off, keep digging, make readers go “Holy shit!”

Or something like that. But I don’t think I’m wrong.

Whatever he would say, his eyes would be smiling.

Guarantee it.

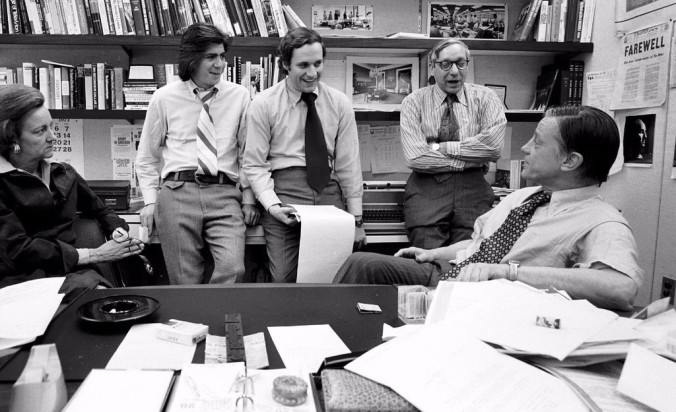

The movie thing. Going clockwise from Tom Hanks (Ben Bradlee). David Cross as Howard Simons is the first person past Hanks’ left shoulder.

The real thing. From left to right: Kay Graham, Carl Bernstein, Bob Woodward, Howard Simons and Ben Bradlee, a pic taken in the days of WaPo’s Watergate investigation.

Love reading your stories and always look forward to them. Straight from the heart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kari, thanks for reading. And thanks for subscribing. Always good seeing your name. And how are you?

LikeLike

Hey, Jeri. This brings back a lot – not least how nice it is to see your byline. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lucia, my Choir Practice member, so … so great to see in this thread. And how are you? Update me when you get a moment. As for the symbolism of that pic, I know we drank buckets of alcohol. But boy, we had fun, huh?

LikeLike

Wow!! What a great piece! I never had the good fortune to meet Howard Simons but I have heard plenty about him. I have been working on a magazine at the Nieman Foundation since 2009.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow backatcha, Jan. How are you? And tell me about this magazine. Would love to hear more. And you as well

LikeLike

Not a lot these days. I’ve aged out of travel — I never married, so I got to work in London, Kabul, Seoul, and Hong Kong — and now my most interesting times are when, as the oldest sister, I get to claim to be head of my family. I’m still in touch with Pat Washburn and Shari Kahn and Jan Gardner, with whom I also worked at the Globe and now Harvard (me part-time only). All three of them are brilliant, totally awesome women. Did you read Shari’s book?

We had a blast. I loved you people and I loved those times. How have you been and what have you been doing in, oh, the last 30 years?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Busy. That’s my answer — and your answer, too.

My “About” on my blog will break it down for you, in journalistic shorthand. But I’m good, a Southerner seeped deep in my bones. But I hold close to my heart our time together in Boston, where we worked so damn hard for little money and learned so much from the people around us. Like Jan.

And now, like some sepia-toned photo, I see those times as a scrapbook memory of a time when we were learning, growing, making mistakes, working long hours and making Friday night at Whitey’s apartment a time when we were wide-open, loud and proud.

And today, as a married father of two teenagers, dealing with responsibility and feeling the slow march of time, I look back to those times we had together in and around Rte. 9 as pretty damn special.

LikeLike

Lucia, miss you. Hope that helps, Choir Member.

LikeLike

I love, love your line about being a newsroom expat. And I miss you, too.

LikeLike

We must raise a glass to you, Jeri Rowe, and to Choir Practice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let’s hope we’re in tune.

LikeLike